An integral approach to evolution & healing

“Paititi”, in Quechua, is an enlightened realm manifested through the awakening of our shared human heart.

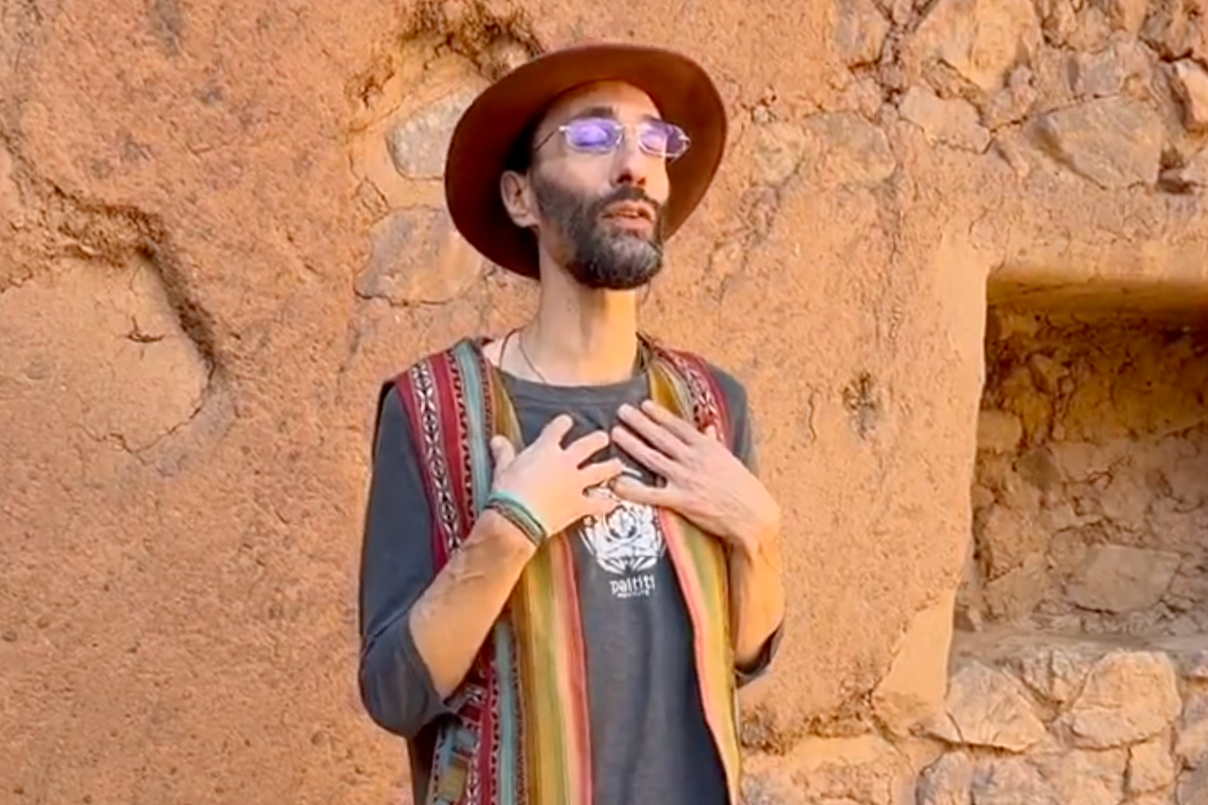

Paititi Institute supports people in awakening their innate potential by transforming life’s challenges into essential human qualities. Rooted in Amazonian, Andean, and Tibetan wisdom traditions, our time-tested approach guides balanced, purposeful living.

Our transformative courses at Paititi Institute invite you to embark on a journey…

Primordial Breathwork™

The breathwork sessions are guided by Roman Hanis who has facilitated this practice since 2003.

Alchemy of Immortality QiGong

This Alchemy of Immortality Daoist QiGong / Andean Art of Being Series for awakening greater vitality in your life.

Evolutionary Blueprint

Explore your own heroic inner journey through life via video talks, reading materials, self inquiry & reflection.

Beyond Ayahuasca

Unlocking the Evolutionary Science of Indigenous Amazonian Wisdom to Access Your Highest Potential

Traditional Ando-Amazonian medicine man takes readers through the three main pillars of Amazonian indigenous teachings, and through a deeper place of transformation and healing with insights and step-by-step guidance.

Supporting the Yagua tribe

A portion of proceeds will be donated to our Yagua Cultural Heritage Center and Indigenous School initiative, helping preserve indigenous culture and wisdom of the Amazonian Yagua tribe. To provide tourists with deeper meaning and knowledge about culture.